Liz Ross is a veganic gardener who studied ecological horticulture and food justice on a 30-acre farm at the U.C. Santa Cruz, Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems program, as well as permaculture at Occidental Arts and Ecology Center. Liz was born and raised in the Caribbean, where her family owns 300 acres of agricultural land in a rainforest, growing mainly cacao, fruits and bamboo. She is the Founding Director of Rethink Your Food, a registered charitable NGO that creates campaigns that encourage the public to become more involved, conscientious eaters. RYF focuses on action-driven campaigns and provides information about eating and growing food without animal exploitation. The following is based on an interview with Nassim Nobari.

Liz Ross is a veganic gardener who studied ecological horticulture and food justice on a 30-acre farm at the U.C. Santa Cruz, Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems program, as well as permaculture at Occidental Arts and Ecology Center. Liz was born and raised in the Caribbean, where her family owns 300 acres of agricultural land in a rainforest, growing mainly cacao, fruits and bamboo. She is the Founding Director of Rethink Your Food, a registered charitable NGO that creates campaigns that encourage the public to become more involved, conscientious eaters. RYF focuses on action-driven campaigns and provides information about eating and growing food without animal exploitation. The following is based on an interview with Nassim Nobari.

When did you attend the UC Santa Cruz Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Program (CASFS), and what are the students being trained in?

I attended CASFS in 2018. We were 49 apprentices living together in an intentional community and learning sustainable farming, with a certain percentage that focused on food justice as it relates to the structural and economic problems faced by farmers and farmworkers. It was a six-month program of mostly field work, and some class work that included amazing speakers and panelists. We had farmworkers, farmers, a soil scientist, a biologist, an agronomist, experts on the farming business, and so many others. I would say probably about half of us wanted to be farmers. Others were interested in school gardens, community gardens and working in food justice or related fields.

Why did you decide to study agroecology?

I wanted to expand on my existing knowledge about the history and politics of farming in the U.S., and about the current concerns of farmers and farmworkers globally.

Liz Ross with Seed the Commons’ Chema Hernández Gil, on a visit to the CASFS farm in 2018.

I also wanted to learn sustainable farming through an agroecological perspective, which takes a more conscientious approach to changing our current unfair food system. While in the program, I felt that the agroecological approach to the practice of farming wasn’t emphasized enough. We were not told that such and such is what agroecology is versus, for example, what organic farming is. Having said that, I learned the basics of how to operate a production farming business. I wanted to learn the fundamentals to then expand on my own to learn how to grow food veganically, which is without depending on chemical inputs, and on manure and other farmed animal inputs, including from fish. Veganic farmers also work with the existing ecology (flora and fauna) around the land. This method of growing food is also known as stock-free farming or plant-based ecological farming. I use these terms interchangeably.

I think that plant-based ecological gardening and farming is the way of the future and can be sustainable and self-sufficient.

Can you speak more about some of the inputs used on the farm at CASFS?

They bought plant-based soil amendments, like alfalfa meal. They also bought seeds from smaller companies, since it’s difficult for most commercial farms to grow crops for harvest and also for all of their seeds. They used fish emulsion and feather meal, and the manure came from a local horse stable and a local chicken farm. Buying these soil amendments (from outside of one’s farm) is also common in other parts of the world, including in the Caribbean, but you can’t always get that stuff locally. It’s costly and it may be contaminated.

Crop diversity at CASFS

Many farmers and gardeners don’t have access to nearby animal farms or horse stables, so the global demand for animal inputs (including from fish) helps to keep industrial animal agriculture (factory farms) and industrial fishing operations in business. We can produce healthy crops without these kinds of animal inputs, however. Veganic farms use local resources such as green manures and even humanure, as well as biochar, woodchips, mulch, compost, and ecological methods to keep the soil healthy and rich with biodiversity, and they are producing healthy yields.

Factory farms breed an unconscionable level of violence, but so do the smaller animal farms, except on a smaller scale. For example, we got chicken manure from a smaller chicken farm under the label “free-range”. I learned that the first few weeks of the chickens’ lives were in cramped cages. I wanted to go there and take photos but I couldn’t. I didn’t go. But the apprentices who were there told me it looked horrible. They were pecking each other, and the ground was filthy. They said you can see the feces all around. This, to me, means that the chickens were also inhaling chemicals from their poop, which then goes into their bodies, which people then eat. After the first few weeks, they let them out. The reason why they don’t let them out in the beginning is that the chicks are too small to live by themselves. They can be eaten by other animals, picked up by birds, and they can be susceptible to harsh weather, while they’re just babies. Even on that so-called beautiful, free-range farm, which obviously kills chickens for their body parts, the first weeks of a chicken’s life are pretty horrible.

What technical challenges have you encountered, especially in terms of relationships with wildlife?

One challenge that I experienced in the apprenticeship and in many other food justice spaces is that there is no discussion, beyond the concept of pest control, about how to relate to the nearby wildlife who feed on the food that we have basically made available to them on farms. In some cases we have created an overpopulation with this abundance of food. For CASFS, it was an overpopulation of gophers and ground squirrels. I would like to see farmers and researchers look for better ways to handle animals who visit nearby farms to feed, instead of viewing them as pests to annihilate in the most convenient way.

I remember, we were standing in the field during a class, and, two feet away just behind me, I heard “SNAP!” Someone then pulled out a gopher who was suffering from a trap around their neck. Gophers are hemophiliacs. Their blood doesn’t clot to promote healing so, instead, they can bleed out [to death] when cut. These traps aim to snap their necks without puncturing them. This results in a quicker death with supposedly less suffering.

Gopher trap (CASFS)

Gophers also get killed when the tractors plough the soil. I’ve seen gophers and ground squirrels get thrown out of their ground tunnels from the force of the plough and many of them are cut up and don’t die immediately. I also noticed that hawks fly above the tractor during these moments, waiting for those injured and vulnerable gophers to land on the ground. They then swoop down and grab some with their claws, but not all of them get picked up.

My challenge, in general, on the farm was just being in a space in which the lives of these mammals were not a priority. Some veganic farmers have implemented better methods of growing food without the use of traps that kill or maim wild animals. You [Seed the Commons] have spotlighted some of these farmers in your work.

How does agroecology constitute a response to social injustice and environmental devastation?

Agroecology is an alternative to the Green Revolution. The Green Revolution is a model of farming that relies on and promotes large monocultures, chemical inputs and fossil-fueled machinery. It also promotes seed patents and GMOs, and pushes farmers to depend on a handful of multinational corporations for supplies or inputs. Corporations and philanthropists promote it as their solution to global hunger, and it is the dominant method of agriculture today.

CASFS greenhouse

Under the Green Revolution model, however, farmworkers are paid low wages, tend to endure horrible conditions, and experience physical and mental abuse. For example, I listened to farmworkers who worked on a large farming operation in Central California that sells produce to a multinational food corporation. It was difficult to listen to their stories about working in the California heat without having adequate access to drinking water and enough toilet breaks. When the driver of the water truck decides to leave to go wherever for whatever the reason, they are left without water. No water truck to replace that truck that just left. It’s very sad!

We’ve also lost at least ninety percent of the varieties of many crops as corporations now control so much of the kind of food that is sold in supermarkets, and even at farmer’s markets. The Green Revolution model also favors government policies and financial perks that advance multinational corporations (Big Ag) over smaller farming operations. It’s a model that is invested in extracting resources without concern for the welfare of our soil, water, humans and other animals. Its effects have contributed to deforestation, global warming and pollution of our air, land and waters.

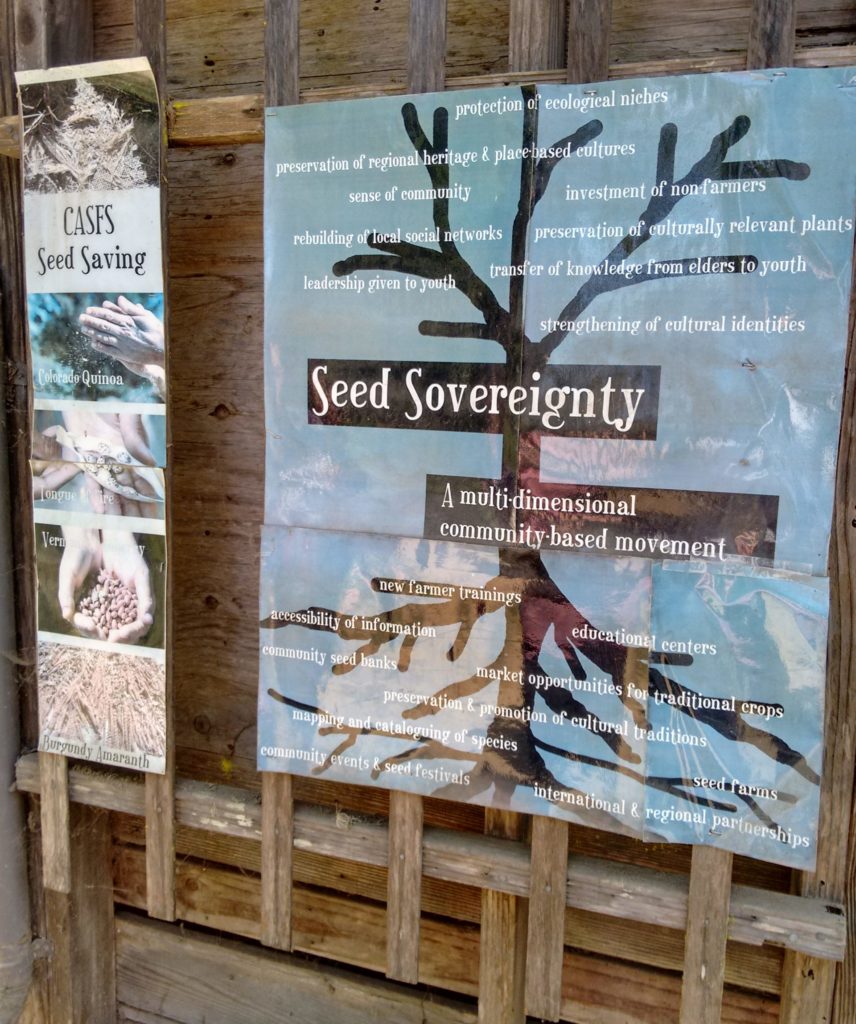

Agroecology works counter to the corporate extraction and bottom-line profit model, so that farming becomes about the community – community resources, community exchange, community creating jobs – and so that smallholder farmers can make a decent living. Food should be another way that people can connect with each other, with other animals and with the ecosystem, which are all part of a community, including farmers. Agroecology is about keeping food centralized in the community as much as possible, then looking at imports and exports from farming operations not monopolized by Big Ag. It means using indigenous sustainable farming practices with ecological science, to maintain healthy soils. It means seed sovereignty. It means food sovereignty.

Poster created by a CASFS farm manager for a class on seed sovereignty.

The Green Revolution changed the way our food system operates among communities, businesses and governments to become more dependent on Big Ag. By understanding its purpose, we can see why farmer coalitions, such as La Via Campesina and Landless Workers’ Movement, mobilize to push back and create change through agroecology, because it can change the way communities, businesses and governments operate a food system to benefit communities and farmers.

So, I think you have to really understand what is going on so that when you are walking through this system and farming, and working within your community, and buying food, and growing food yourself, that you are conscious that this is part of a movement through which we can find meaning, and through which we can reaffirm our identity and dignity, because we all deserve a healthy, equitable food system.

A healthy agroecosystem is a space with an abundance of different plants and animals (CASFS)

If we are not paying attention to how our current food system operates, then it is going to be morphed into something similar that we blindly accept as progress. For example, Walmart and Amazon now offer door-delivery food packages that compete with CSAs (Community Supported Agriculture) that small farmers rely on in their area. So, Community Supported Agriculture has now become Corporate Supported Agriculture. This is yet another way to monopolize the market to increase their profit and squeeze out small farmers.

If you don’t know what’s going on, you’re less likely to make better decisions that are within your reach, and less likely to support organizations and policies working for change.

Your family in Trinidad and Tobago owns agricultural land. With that perspective, do you think that agroecology would be readily appealing and adoptable for farmers and landowners in the Caribbean?

Some farmers are moving towards agroecology. They are exchanging and sharing resources and ideas, and selling organic produce locally. Some farmers have, over time, weaned their crops off of chemical-based inputs to now have a sustainable organic food production business. However, these farmers are not the norm.

Farmers are interested in knowing, first, that they can make a decent living. So, it’s not easy to make changes to one’s farming methods if that might, in the beginning, slow down the process, even if those changes might produce more and healthier yields in the long run.

For starters, I think there needs to be more awareness about the harmful effects of chemical-based inputs, and that there are alternatives. With this awareness, maybe people can push for policies that can support ecological farming, especially closed-loop systems, because those systems require minimal to no external inputs. If we can show success stories first, then others can see that this is doable.

Another issue is that many Caribbean countries import around seventy percent of their food and this includes meat, which can come from factory farms in the U.S., South America and even as far as New Zealand. When I talk to Caribbean folks about the horrible conditions in factory farms, contaminated water and deforestation, and I show them videos, some of them say, “Wow, I didn’t know that.” So, similar to many people globally, a lot of them are not aware of the toll it takes to provide for this high global demand for meat, dairy and eggs.

Veganic tomatoes grown in Liz’s home in Florida.

I also think there needs to be more spaces where farmers and gardeners, who are knowledgeable about indigenous farming practices, share information with other farmers and gardeners, and that it gets documented. In documentation we can see the power in, “OK, you know this, I know this, and you know this. Wow! We have a lot of knowledge here, so we can come together and figure this out.”

What has been your experience in the food justice movement as a vegan, so far?

The food justice movement in the U.S. is very much into animal-centered regenerative farming. It’s the big thing now. It has become the default in food justice. Its general identity seems to be connected to a sense of pride in eating animals (especially locally raised), and the idea that farmed animals (especially cows through what is known as holistic management) will save the planet from global warming. In these spaces, there is a general mindset that promotes a dependence on breeding and raising farmed animals who are non-native to the area, and intentionally moving these animals around the land to regenerate the soil (because they don’t tend to roam in the same way native wildlife do), and then slaughtering them for food.

Fresh off the vine!

Taking this a step further, for example, at the farm, a couple people talked about how they felt that their experience of taking part in slaughtering a pig was important to them, similar to an initiation or spiritual awakening. This way of thinking is usually tied to a concept of a “mutual” spiritual connection and sense of gratitude toward raising and slaughtering them. Added to this, sometimes paying homage to the ancestors are drawn in to emphasize this spiritual expression and it acts as the reinforcing justification for the violent act – the slaughter and the tasting of flesh.

I think this is a false sense of connection because the animals aren’t willingly colluding in their own demise. Here, the animal is being objectified through a speciesist frame, and rituals and ceremonies are playing a role in the attempt to psychologically buffer the reality that one is taking someone else’s life against their will, even when plant-based food is readily accessible.

Regardless of what culture you identify with, spirituality and ancestral traditions have never been good reasons to justify objectifying, exploiting and/or killing anyone. Unfortunately, they have been used to harm humans and other animals for millennia.

Why not, instead, celebrate the components of spirituality and tradition that promote nonviolence? Why not, instead, update celebrations and rituals with plant-based food that our ancestors have felt connected to? Wheat, maize, dasheen, cassava, potatoes, berries, mangoes, beans, lentils, peas, tomatoes, rice, pumpkin, squash, hemp.

I would like to think that we can get to a point where people value the sentience of animals, because, among other similar things, they do suffer like us. Don’t they have a right to share this planet with us without being exploited for the taste of their flesh or for their baby’s milk? Because these animals experience sentience (which includes the capacity to be conscious of one’s suffering), I’m not seeing good reasons for compartmentalizing some of them as food while others are valued as companions to love. Once people acknowledge this reality, maybe then we can build a local food movement that understands that shipping beans from Ohio to California is a more ethical solution than killing backyard chickens, and not a contradiction to building a better food system.

Liz’s rosemary, grown veganically

Going back to regenerative farming. There are plant-based ecological methods to grow food sustainably; and rewild damaged lands through natural rewilding that creates spaces to bring back indigenous wildlife to restore ecosystems and hold carbon in the soil. This is already happening and some farmers are already practicing plant-based ecological agriculture around the world.

What are your thoughts on practicing agroecology as a vegan?

In my environment, agroecology looks the same as what other food justice proponents advocate for. A few immediate things that come to mind is, supporting local farmers and farmworkers to make a decent wage and in good working conditions, supported by a society and government that understands that a focus on “cheap” food comes with dire consequences. It’s about creating policies to increase diversity in land-ownership and to make it easier for smallholder farmers to acquire agricultural land. It’s about neighbors exchanging food they grow in their garden. It’s farmer cooperatives, more farmer’s markets and more CSAs in many more locations so that everyone (buyer and farmer) can have access. It’s governments prioritizing small grocery store businesses. It’s cities and towns having efficient composting systems. It’s using local plant-based inputs. It’s about creating a more efficient city waste management system that can use human waste for energy and fertilizer. It’s policies that take corporate control out of our food system. I could go on. Agroecology can look a bit different in other places.

What other challenges do you foresee as you start your journey in agroecology?

Making a paradigm shift is always a challenge because you’re asking people to consider something new, something different. Farmers, including livestock farmers and fisherfolk, have to believe that there are benefits (that there is something in it for them) to transitioning to plant-based ecological agriculture, and one that doesn’t exploit animals in its farming practices. Obviously, this shift in consciousness will take generations to become the norm as we gradually move toward a global food system that supports access to healthy plant-based food for all, and it has to start in people’s minds. It has to become part of our values and our culture, not just within the farming community but on a broader scale.

Putting things into perspective, there is a huge problem that needs to be immediately addressed as a collective, which is our global dependency on factory farms and the industrial fishing industry. This unnecessary industry is contributing to the destruction of our planet, and it is the largest cause of animal abuse in history, therefore, in my view, a collective boycott is imperative. This crisis is one of the reasons why I founded Rethink Your Food.

Putting things into perspective, there is a huge problem that needs to be immediately addressed as a collective, which is our global dependency on factory farms and the industrial fishing industry. This unnecessary industry is contributing to the destruction of our planet, and it is the largest cause of animal abuse in history, therefore, in my view, a collective boycott is imperative. This crisis is one of the reasons why I founded Rethink Your Food.

Another challenge for vegans and nonvegans alike, is how to create local economies that function well so that we can get the nourishment that we need with as little travel as possible? So, for example, in the Caribbean, if more efficient food exchange networks can be implemented through CARICOM, including policies that would make trade easier for farmers and businesses that sell local food products within the region, then we can reduce the amount of imports from further distances. Having said that, to be realistic, it doesn’t mean that we cannot also import food from outside our region. It means we need to have more of our food travel shorter distances than they currently do, while keeping a viable food trade market in the region.

Do you see a role for the animal rights movement in helping address any of these issues?

There is a huge body of research available on how to influence social and political change that many animal justice organizations and individuals are utilizing to help reduce animal exploitation. However, some of these groups (and some individuals) promote the idea that “going vegan” can eliminate world hunger, and this way of thinking can help to disconnect the animal justice movement, in general, from people working towards an equitable food system.

Many experts say that there is enough food available to feed the world, yet people are still going hungry. So, the idea that if we take animals off our plates we will contribute to solving world hunger by making more food available reveals a narrative that appears to align with Big Ag’s marketing pitch of food scarcity. Big Ag pushes this to justify expanding and monopolizing our food system and this in turn drives more farmers out of business or into poverty.

The students at CASFS dried amaranth and quinoa plants with seeds in the greenhouse. Afterwards, they would shake them in a bucket for the seeds to fall off.

Big Ag cannot succeed without large monocultures, chemical inputs, GMOs, unfair subsidies and free trade agreements, seed patents, food waste, land grabs, damaging our land, and paying people low wages while the majority of the profit goes to a handful of multinational corporations. It cannot succeed without trading staple crops, such as wheat, maize and rice, as commodities tied to price speculation on financial markets. These components can contribute to poverty and hunger, and do not go away if all arable land is now used to grow crops to sustain a plant-based diet. The Green Revolution was supposed to eliminate world hunger but it did not, even in today’s environment of abundance.

On the farm, there were only two of us who were [ethical] vegans and any discussion about the rights of animals in that environment was taboo. In this environment, animal justice is not yet recognized as a legitimate social justice issue.

So, I think it is important that more animal justice advocates, who are part of the movement for an equitable food system, have a basic understanding of the systemic factors that have contributed to poverty as it relates to hunger. This will likely help us to connect with more nonvegans in food justice and create more meaningful dialogue.

I look forward to seeing more organizations throughout the world advocate on behalf of veganic farmers on a policy level. I would also like to see more individuals raise awareness, and advocate for, veganic farmers and gardeners. Support the farmers financially, promote their farms and gardens on social media and learn about why they chose to grow food this way. It is nice to see that this is beginning to happen now. Perhaps in the near future, we will be able to watch a documentary spotlighting the benefits of plant-based ecological agriculture to our ecology, health and climate.

I enjoy growing food veganically. My experience of the joy I feel when creating my own plant-based compost, and watching the plants grow and interact with the worms and other workers in the soil, while providing them with my love, care and attention, is beyond words.

Do you have any thoughts for nonvegans in the fair food movements regarding areas that they need to improve?

If we are looking to create a better food system, then let’s look at those fundamental values that make this exploitative system work well, and let’s not perpetuate those values. Let’s examine those values of exploitation that spill over into building a fair food system. That includes reevaluating our relationship with other animals. The animals who people eat and the animals who are killed on farms (as collateral damage) are sentient beings. Biology and science have already determined that, not that we need science to see what is obvious.

Liz’s veganic herb garden